She gained notoriety and acclaim in the new field of investigative journalism by going undercover at New York’s Blackwell Island Asylum as a patient to expose widespread abuses of its female patients. Her reporting forced the asylum to implement sweeping reforms.

After her marriage to industrialist Robert Seaman, 40 years her senior, Nellie took a keen interest in manufacturing. She took charge of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company a leading manufacturer of enameled kitchenware, milk cans, and like products. Iron Clad products were advertised as being made in factories “Owned exclusively by Nellie Bly – the only woman in the world personally managing industries of such a magnitude.”

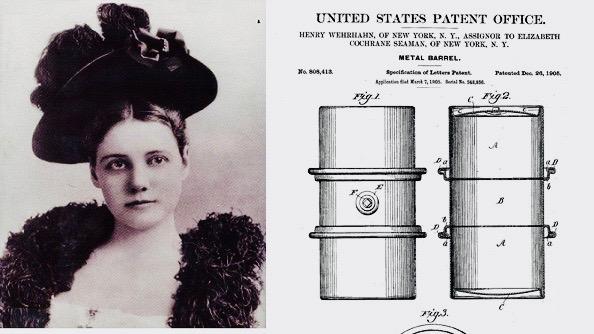

At this time, traditional wooden barrels were used for shipping and storing everything from food to gunpowder to oil. The booming oil industry needed a more practical solution for leakproof and durable containers. The Standard Oil Company designed a metal drum which was an improvement over the wooden barrel, but their design was poor and prone to leaking. Nellie Bly made it her mission to solve this problem saying, “I determined to make steel containers for the American trade.” One year later, with the help of company superintendent, Henry Wehrhahn, the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company patented the first commercial metal barrel. Nellie recounted, “My first experiment leaked and the second was defective because the solder gave way, and then I brazed them with the result that liquid inside was ruined by the brazing metal. I finally worked out the steel package to perfection, patented the design, put it on the market, and taught the American public to use the steel barrel.”

Nellie eventually returned to her first love, journalism, and continued to cover women’s suffrage. She died in 1922, two years after women achieved the right to vote. We remember her as a trail-blazing woman and a great contributor to our industry.

Recent Comments